Rediscovering Trent Park House: a trip to the National Archives

Rachel Pistol and Trent Park House volunteers at the National Archives

A guest blog post by Dr Rachel Pistol, former academic research lead for the Trent Park House Museum project. Rachel is an expert on refugee history and Second World War internment in the UK and the USA.

On Thursday 27th April, 2023, a group of 14 research volunteers travelled to the National Archives, Kew to see what they could find about Trent Park House during the Second World War. The team of volunteers spent time learning about using archives, the history of Trent Park, and enjoyed spending time in the reading room looking at original documents from the 1940s. Lots of different types of files were looked at, and the volunteer team continues to visit the archives to unearth more!

Rachel Pistol and Trent Park House volunteers at the National Archives

Below are some of the highlights of what has been discovered so far.

Many of the files at Kew are incredibly thick and crammed full of transcripts of conversations made by German and Italian Prisoners of War (POWs) who were unaware their talk was being listened to and translated by the army of ‘Secret Listeners’ housed at Trent Park, Latimer House, and Wilton Park. Many of the secret listeners were German and Austrian refugees who had fled Nazi persecution on the continent, found refuge in the UK, been interned in 1940 as ‘enemy aliens’, and then had joined the British Army on release from internment, where many went on to join the intelligence services. These refugees were an incredibly important asset to British intelligence, bringing their language skills and desire to see the Nazis defeated, and these files contain much on their truly valuable work – information that transformed the British war effort.

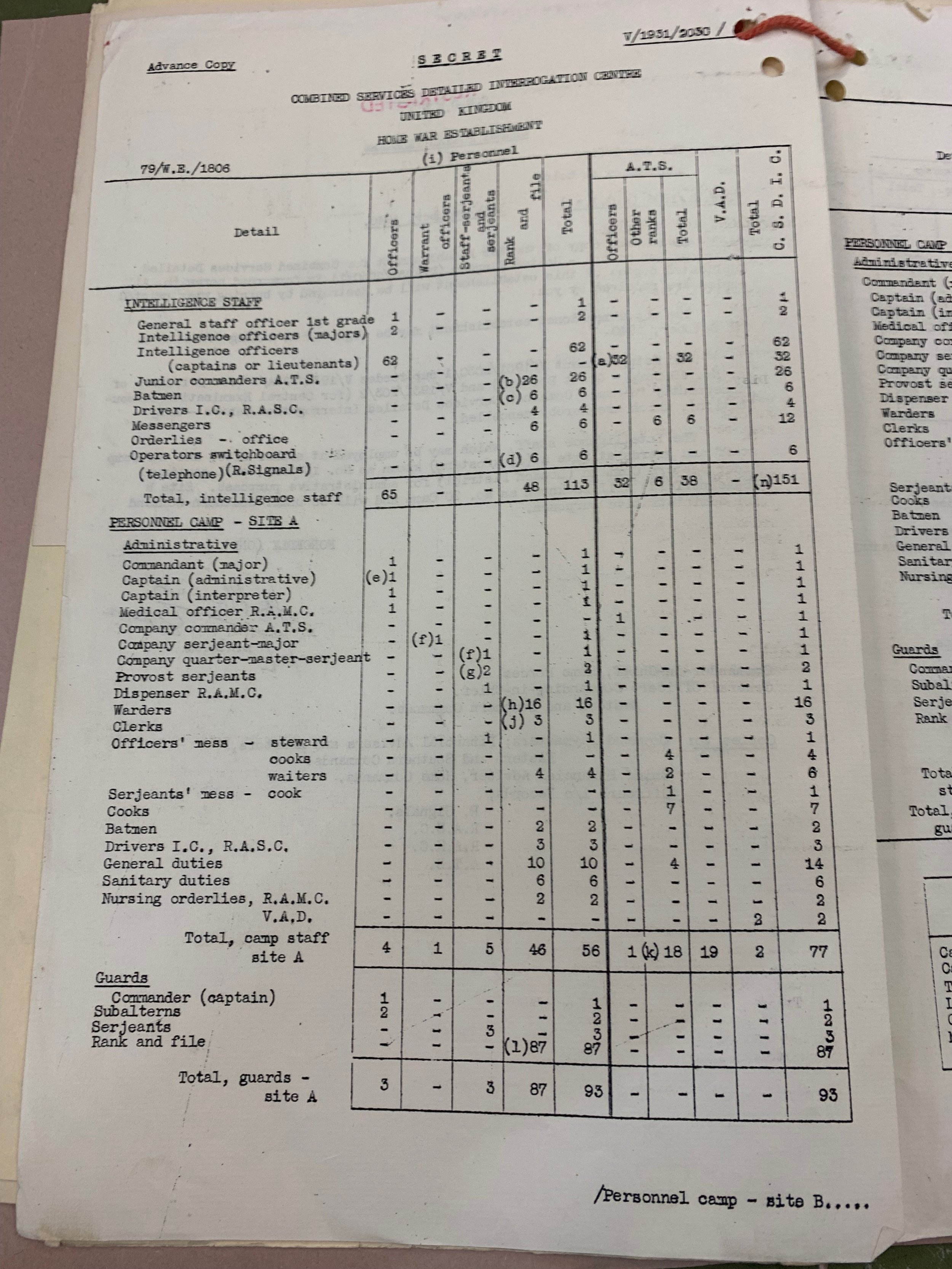

Trent Park was known as ‘Site A’ in files (WO 208/3540 from the National Archives, Kew)

Part of the research process is to weed out the files that do not have direct relevance to Trent Park from those that do. Descriptions on the National Archive’s catalogue for each file are often only based on what appears at the front of a file – so if a file contains several hundred pages, there is no way to know what exactly is in it until you read it. As Trent Park and the other sites of secret listening were top secret, they are often not referred to directly, but through other terms such as their location. In the case of Trent Park, this means looking for references to Cockfosters.

Historical research is a form of detective work, and this can involve lots of time scouring the internet and archives for obscure references that may or may not exist. However, when you finally find something, the buzz is so exciting that it hooks you into looking for more, as our research volunteers can confirm.

Files have been found with biographies and photographs of some of the German POWs who spent time at Trent Park including information about the individuals’ army careers and where they were captured. These files also contain handwritten comments on what conclusions had been drawn from listening to their conversations, such as whether someone was pro- or anti-Nazi, guilty of war crimes, polite, snobbish, troublesome, or “a bore”. Sometimes additional comments were noted, which could range from “ardent member of the camp string quartet” to “wiped out the entire Russian village when his pet dog was accidentally shot”.

Some of the material included in the files, given that acts of war are covered, make hard and unpleasant reading, such as the comment above. Many incidents of war crimes were discussed in private by the POWs, believing that such conversations were private, and these files are full of such references.

“Confidential.” WO 208/5628 from the National Archives, Kew

Trent Park was designed to deceive its prisoners in many different ways, including trying to give the impression that all was well in Britain and that there were no deprivations as a result of the war. This clearly had quite an effect on some of the POWs, one of whom talked to his roommate about how amazing the provisions were, saying that in “a country where potatoes, bread, flour and coffee are not even rationed, [the British] don’t even know what hardship means!” His roommate agreed, talking about how amazed he was that there was “nothing but white bread! When I had my meal I couldn’t make it out at all.” Another prisoner was heard remarking that the “nicest people on earth are the English race. It’s a calamity that we have to fight them.” Not all of the prisoners were so positive about the British, of course, but there were many who appreciated the treatment they received at Trent Park.

Morale in Germany came up as a regular topic of conversation, giving the British valuable insights into what was happening abroad. As the war went on, more and more POWs expressed their dissatisfaction with Hitler, and how much they wanted to return home and for the war to be over.

In terms of the actual site at Cockfosters, files have been found that explain the use of the site, the names of the personnel who worked there, and what was to be done with the site long term. Discussions were had as to whether Cockfosters was a safe enough location given its proximity to London and bombing raids, though it was decided that the site would continue to be used for intelligence throughout the war. Some of the files focus on the administrative side of the running of the camp, including who was in charge of the intelligence staff, the maintenance of the building and so on.

Exploring the archives at the National Archives

Together, all these pieces of information provide pieces of the jigsaw to help build the full picture of what happened at Trent Park during the Second World War and will help with the creation of oral histories and eventual onsite museum. Names that have been discovered are helping to provide leads to our oral history team who are interviewing relatives of those who worked at Trent Park as well as those who have memories of the site in general. More is yet to be discovered, but there is a mountain of paper to wade through first!

None of this work would be possible without the work of our wonderful team of research volunteers, the many hours they have spent in the archives so far, and the gems of history they have already unearthed. The quotes from the documents in this blog come from research conducted by Belinda Sutherland, Charlotte Regan, Diana Medlicott, Gillie Christou, James Cooke, Jason Amiss, Michael Pendock, Rachel Wilkes, Ros Brain, Sarah Hargreaves, Sheila Puckett, Stephen Dalziel, Sue Elliott and Vicky O'Connell, and we are extremely grateful for their passion on this project.

Piecing together the information at the National Archives

The Oral History Project at Trent Park House is funded thanks to a £225,000 grant from The National Lottery Heritage Fund. The project aims to preserve the rich history of the house through the collection of stories and memories from those who have a personal connection to the Grade II Listed mansion.